Education is critical to the success of any nation. Higher education attainment tends to be associated with an increased likelihood of being employed, being in good health and reporting life satisfaction (OECD 2016b, 2018).

It seems timely to examine the changing face of Australia’s education system, looking back at the historic 2011 Gonski Report and 2017 review and to the current plight of Australian universities in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The Gonski Report – The 2011 Review of Funding for Schooling

In 2010, the Australian government commissioned the historic Gonski report into school funding. The panel received more than 7000 submissions and visited 39 schools across the country. The report’s findings showed that the performance of Australian students had declined at all levels over the last 10 years. In 2000, Australian was outperformed by only one country in the areas of reading and scientific literacy and only two places behind the top performing schools globally in maths. By 2009, Australia was in seventh place for literacy, and thirteenth for maths.

The report found that there was a large performance gap between the highest and lowest students, suggesting that Australia’s lowest performing students were not meeting acceptable standards of achievement. This low standard was found to be directly linked to educational disadvantage, particularly among students from lower socio-economic and Indigenous backgrounds.

The Gonski report found that state and federal governments needed to work together more closely to ensure that students are not falling through the gaps. By working together, the report suggested, government could ensure funding was coordinated effectively. A new funding model based of a ‘per-student’ amount was suggested for all students, ranging from $8,000 per primary student and about $10,500 for secondary students.

Beginning in 2014, in accordance with the Australian Education Act 2013, the Australian Government began to deliver funding to Australian schools on a needs basis, ensuring that all schools were appropriately funded to give equal education to their students, regardless of their background.

Gonski 2.0

In 2017, the Australian Government established the Review to Achieve Educational Excellence in Australian Schools. The Review was asked to recommend ways that Australia could improve educational outcomes, in order to return to its place as one of the top education systems in the world. The report made 17 key findings, including:

- Achieving educational excellence in Australian schools will require a focus on achievement through learning growth for all students, complemented by policies which support an adaptive, innovative and continuously improving education system.

- Early childhood education makes a significant contribution to school outcomes.

- There is strong and developing evidence of the benefit of parent engagement on children’s learning.

To address these findings, the review made five key recommendations. These were:

- Laying the foundations for learning (by coordinating a seamless transition from early education)

- Equipping every student to grown and succeed in a changing world (by revising the curriculum, emphasising early-year literacy, numeracy and general capabilities)

- Creating, supporting and valuing a profession of expert educators (encouraging professional collaboration, improved career pathways and a national teacher workforce strategy)

- Empowering and supporting school leaders (by revising the Australian Professional standard for Principals)

- Raising and achieving aspirations through innovation and continuous improvement (encouraging better forms of self-review and external quality assurance)

In 2019, proficiency in literacy among 16-65 year-old Australians remained above average. Today, proficiency in literacy remains is below average, with 16-24 year-olds performing the best. Unemployment rates in Australia still remain below the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) average.

Tertiary Education

Established in 1961, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) is an intergovernmental economic organisation founded to stimulate economic progress and world trade. There are currently 37 member countries in the OECD. Education at a Glance: OECD Indicators (OECD, 2019[1]) is the “authoritative source for information on the state of education around the world”, providing data on the structure, finances and performances of education systems. In 2019, the Education at a Glance data found that Australia’s gender gap in tertiary attainment has increased in the last decade. In 2018 it found that 59% of young women in Australia were educated compared to 44% of young men. Calculating the total distribution of 25-34-year-olds with tertiary education, Australia was ranked #7 out of all 37 OECD countries in 2018.

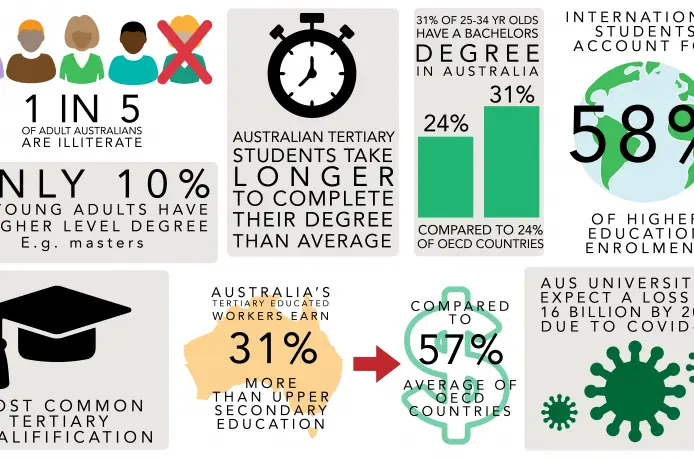

The OECD report 2018 report found that the most common tertiary qualification in Australia is a bachelor’s degree, which was held by 31% of 25-34-year-olds in 2018, compared to a 24% average across OECD countries. Only 10% of young adults have attained a higher-level degree (master’s or doctoral) compared to 25% on average across OECD countries. The report found that tertiary students in Australia take longer to complete their degree than average.

The average earnings premium for a tertiary education in Australia is lower than other OECD countries. Full-time tertiary-educated workers in Australia earn 31% more than those with upper secondary education, compared to 57% on average across OECD countries.

Adults with a master’s or doctoral degree earn on average 52% more than those with upper secondary education compared to 91% more on average across other OECD countries.

Since 2013, higher education enrolments from overseas students have grown rapidly, with enrolments from India and China alone accounting for 58% of higher education enrolments in 2019 (DESE 2020). Earlier this year when COVID-19 travel restrictions were announced for travellers from China on February 1, followed by all foreign arrivals later in March, it became clear how much of Australia’s university sector is now reliant on international students. Universities Australia now estimate that between 2020 and 2023, Australia is looking at a $16 billion loss in revenue.

In August 2020, at least 10 tertiary education institutions were named in an underpayment scandal. Melbourne’s RMIT university has been taken to the Fair Work Commission after not responding to underpayment allegations made by the National Tertiary Education Union (NTEU). After the university’s, School of Management reduced the number of hours that tutors could claim for marking, the union estimated tutors could face losses of $6000 per semester.